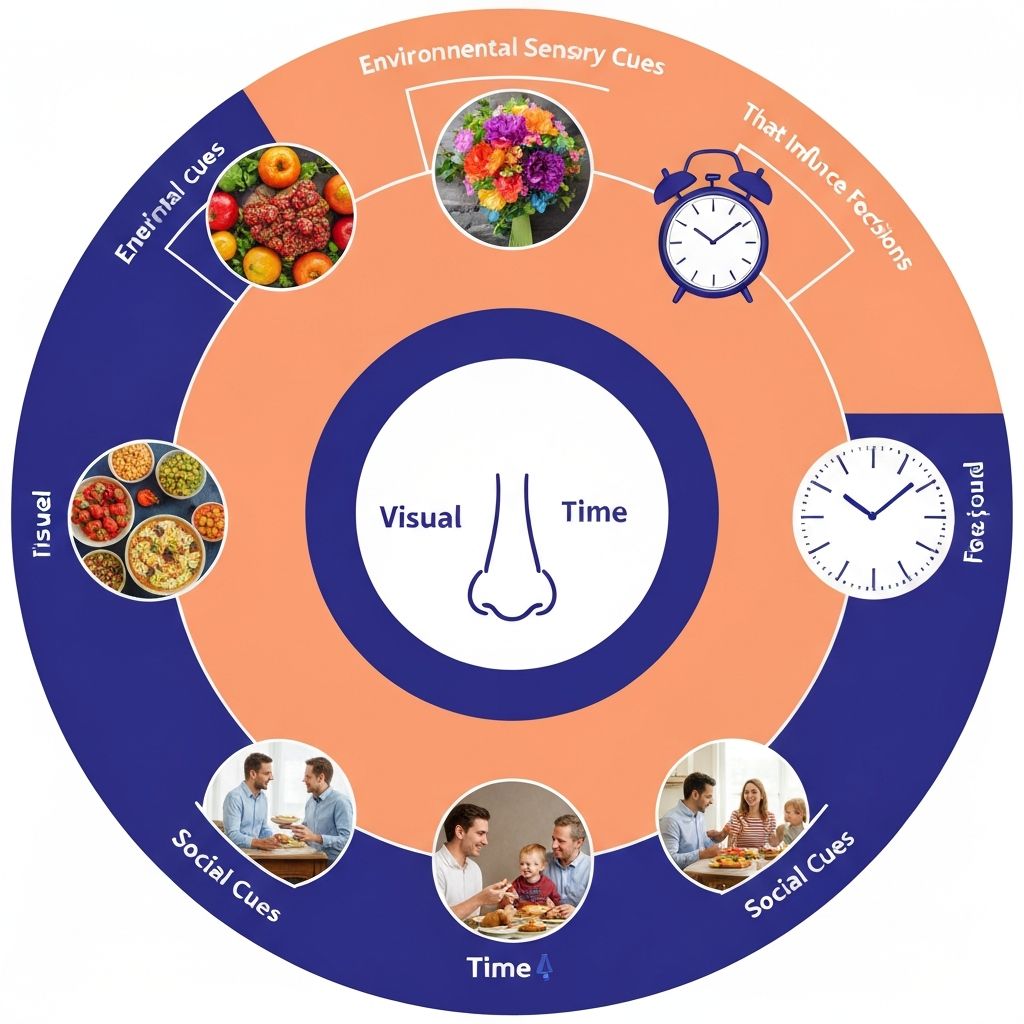

Exploring different types of environmental and sensory cues that shape automatic food-related decisions.

Visual cues—the sight of food, food-related objects, or eating locations—represent some of the most salient cues for eating behaviour. The brain's visual system is highly developed for environmental analysis, and food-related visual information captures attention readily.

Seeing specific foods in familiar locations triggers automatic reaching responses. Seeing others eating, seeing food preparation, or even seeing food-related imagery can activate eating-related neural systems. Visual cues are immediate, direct, and powerful triggers for automatic behaviour.

The sense of smell connects directly to brain regions involved in emotional processing, memory, and reward. Aromas of food—both actual smells and remembered associations—can activate strong automatic responses. Olfactory cues are particularly powerful because they activate neural systems with minimal conscious processing.

Specific food aromas become associated with contexts and times through repeated pairing. The smell of coffee might automatically trigger morning-routine eating responses. The aroma of particular foods can reactivate entire contextual memories and associated behaviours.

Time itself functions as a powerful cue. The brain's internal timing systems (circadian rhythms) create predictable biological readiness states at particular times of day. Learned associations between specific times and eating mean that time-of-day triggers automatic eating-related responses.

A particular clock time can automatically activate motivation to seek food, even without hunger signals. This reflects learning: repeated pairing of specific times with eating creates automatic associations where time becomes a cue for eating behaviour.

Specific locations develop strong associations with eating behaviours through repeated pairing. A favourite eating location becomes a context that automatically triggers associated eating patterns. Being in that location activates memory systems that reactivate previously learned eating responses.

Spatial layout within locations also functions as cuing: a particular chair, desk, or room section becomes associated with eating, and presence in that location automatically triggers responses.

The presence of other people, particularly in shared meal contexts, functions as a powerful cue. Social eating rituals, shared meal times, and established group patterns create social contexts that automatically trigger synchronized eating responses.

Observing others eat activates mirror neural systems and eating-related brain regions. Social norms about eating in particular contexts become internalized as automatic response patterns.

Emotional states function as internal cues for eating behaviour. Through learned associations, particular emotional states can automatically trigger eating responses. Boredom, stress, or habitual emotional patterns can serve as cues that activate eating-related motivations.

The emotional context in which eating typically occurs becomes encoded, so similar emotional states later reactivate associated eating responses.

In reality, cues rarely act in isolation. Eating contexts typically present integrated combinations of visual, olfactory, temporal, spatial, social, and emotional cues. These multiple cues converge to create powerful automatic responses.

Walking into a familiar eating location at habitual meal time, seeing others eating, smelling food, and experiencing familiar spatial arrangement creates convergent cue stimulation that powerfully activates automatic eating responses. The integration of multiple cue types creates robust automatic patterns.

Individuals vary in their sensitivity to different cue types. Some respond more strongly to visual cues, others to olfactory cues. Some show strong temporal cue responses, while others respond primarily to social or contextual cues. This variation reflects differences in neural systems and learning history.

These individual differences mean that the same environment creates different automatic responses in different individuals based on their particular sensitivities and learned associations.

Educational Note: This article explores how cues function in automatic behaviour for educational understanding. It describes general principles observed across populations. Individual responses to cues vary substantially. This is informational content only, not guidance for modifying personal behaviour.